Choreo is Choreo

A pedagogy of action sequences, pirouettes, and writing

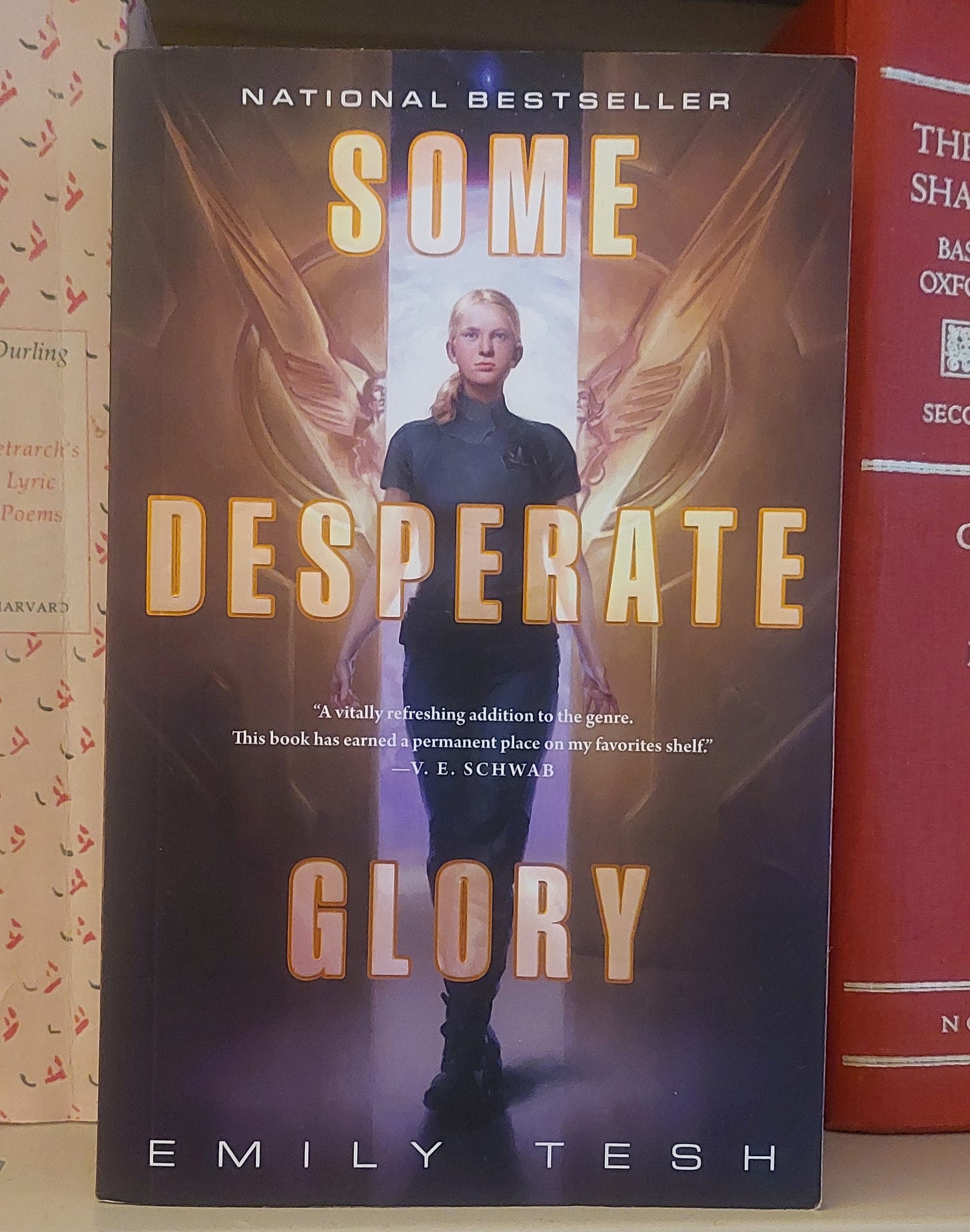

In Some Desperate Glory (one of the best books I’ve read this year), Emily Tesh describes a moment where dance and combat intersect:

“The stick was in their hands, balanced between their long fingers in a relaxed and confident two-handed grip that Kyr recognized, because it was from Yiso’s stick dance. Which, she quickly realized, had never been a silly dance at all. It had been weapons training.” (223)

Kyr, a human, witnessed Yiso, an alien, practicing with the stick and thought they were attempting to dance. Yiso’s combat training is choreographed, like a karate kata, and they aren’t very good at the steps. Seeing a more improvised, and competent, demonstration of staff fighting by an older alien causes Kyr to realize she miscategorized what she saw Yiso doing. Being brainwashed by a cult, Kyr values fighting over dance. Art is “silly”; combat is valorous. The cult on Gaia Station is a reflection of a real—and terrifying—part of modern human society: prioritizing fighting over art. This appears in everything from algorithms that amplify arguments rather than creative work to the Department of Defense becoming the Department of War while the National Endowment for the Arts is gutted.

It’s also a big part of Hollywood: action movies and stars have more money than dance movies and dancers. The budget for action movies like Atomic Blonde (around 30 million in 2017) is considerably more than the budget for dance movies like Suspiria (around 20 million in 2018). Atomic Blonde’s lead actress, Charlize Theron, was a ballerina before she was an action star; a knee injury changed her career path and made her far wealthier. One of the most highly paid ballerinas of all time, Misty Copeland, has a net worth of around 3 million, while Charlize Theron made about 13 million for Atomic Blonde alone. She has frequently compared studying ballet with learning fight choreography for films, including in her Hot Ones interview.

Michelle Yeoh also compared learning dance choreography with learning fight choreography in her recent Vanity Fair interview. Like Charlize, Michelle started out as a ballerina. She wanted to become an action star because fight choreography looked like dance choreography: something she felt confident learning. Both of these actresses reinforce what I argued in my essay about the Ballerina movies: choreography is choreography, whether it’s for a fight or for Romeo and Juliet’s love scene. The movements become muscle memory through repetition. Pedagogically, learning choreography is not a problem-posing process. Much to Paulo Freire’s dismay, learning the steps of a dance or fight scene starts with a demonstration and explanation of the moves, then drilling those moves over and over with your teacher watching and critiquing until you internalize them enough to perform them without the brain’s interference: from the muscles and infused with emotion.

Learning the fundamentals of dance technique, that is, learning the components of choreography (the individual moves), shifts from the dancer observing to the dancer being observed, cued, and given notes by the teacher. To learn a pirouette, you watch your teacher perform a pirouette and receive verbal instruction on how to spot, where to put all your limbs, how to balance on one leg, how to engage your core, which way to turn, etc. Then, you try to do a pirouette and your teacher provides feedback. You probably fail somehow the first time. You try again, and again, and again, until the pirouette is something your body understands without your teacher’s verbal cues, or the echoes of them in your mind. You “bank” the pirouette, in Freire’s terminology: it is deposited into your body (committed to muscle memory) and you withdraw it (perform it) when asked.

Clay Shirky’s essay for the New York Times (copied into a facebook post to avoid paywalling) suggests moving the craft of writing away from the ballet style of pedagogy in response to students’ use of ChatGPT and other generative software. He argues for oral examinations so students can’t use A.I. to cheat. Talking isn’t writing, or dancing. You can discuss how to do a pirouette all day long, but you’re not going to be able to do a pirouette until you practice it. You can talk about writing, but public speaking is a very different skill than assembling sentences on the page. You have to practice your craft: you have to repeat the mundane acts of writing many, many words, having those words critiqued, and rewriting those words. Again, and again, and again until you spin out words like spinning a pirouette committed to muscle memory, conveying emotions, images, and ideas instead of fretting over where to put your hands over the keys.

Learning how to defend an argument with the spoken word is a useful skill. Discussing dance techniques can aid a dancer in learning them. Discussions about fight choreography help ready them for the screen. However, just as Michelle Yeoh and Charlize Theron must practice the actual choreography, you must practice composing, and recomposing, sentences to excel as a writer. You can’t talk your way into a good pirouette or essay. You have to create, analyze, and recreate your art.